Friday, December 31, 2010

Sewell Chan: Economists consider ethics code

We seem as a profession to have a difficult time dealing with ethics--it makes us squeamish, because mainstream economics often celebrates avarice. But one of Adam Smith's earth shattering works was called The Theory of Moral Sentiments, so he wasn't squeamish about thinking about such things as all.

I have within this blog from time-to-time disclosed my relationships when such things might matter to what I am writing. The two most important are with Realtors (when I was a graduate student I worked for the Wisconsin Realtors Association, and I was a consultant on Existing Home Sales in the late 1990s and early 2000s) and with Freddie Mac (where I worked for less than a year and a half in 2002-03). My center at USC has a large number of donor members. I have also consulted for the World Bank. These relationships have been rewarding to me financially and intellectually, and while I like to think I play things straight, I would be foolish to pretend that these experiences have had no influence on my outlook. I leave it to readers to determine the impact of such influence on the validity of what I write.

Thursday, December 30, 2010

How the NCAA undermines the academic enterprise

But part of the academic enterprise is instilling in students the importance of not bullshitting. The NCAA undermines this when it states things like:

Money is not a motivator or factor as to why one school would get a particular decision versus another. Any insinuation that revenue from bowl games in particular would influence NCAA decisions is absurd, because schools and conferences receive that revenue, not the NCAA.But who are the members of the NCAA? The schools! This statement meets Harry Frankfurt's criteria for bullshit, and is an example of why bullshit is harmful. Frankfurt:

Someone who lies and someone who tells the truth are playing on opposite sides, so to speak, in the same game. Each responds to the facts as he understands them, although the response of the one is guided by the authority of the truth, while the response of the other defies that authority and refuses to meet its demands. The bullshitter ignores these demands altogether. He does not reject the authority of the truth, as the liar does, and oppose himself to it. He pays no attention to it all. By virtue of this, bullshit is the greater enemy of the truth than lies are.It seems to me that those of us who have anything to do with colleges and universities have an obligation to avoid bullshit.

Wednesday, December 29, 2010

My colleague Lisa Schweitzer gently scolds me, and then teaches me something about LA Metro project management

First off, it’s a bad idea to conclude anything about work effort based on what you observe by walking by. That’s like the people who judge professors by saying we “only teach two hours a week.” It’s not a valid sample, and it’s very had to evaluate other people’s work effort when you have never done the job yourself— and that’s particularly true of white collar workers passing judgment on blue collar workers engaged in dangerous and often tiring work–during a recession, no less, where anything that extends their work hours has direct implications for their family’s ability to eat and pay rent (unlike salaried work).It is worth reading the whole thing.

More to the point, Richard is mistaken when he concludes that people are not upset. The LA Weekly recently published a story called L.A.’s Light-Rail Fiasco which eviscerates the CEO of the Exposition Metro Line Construction Authority, Rick Thorpe, for salary and his conduct. Rick Thorpe is exactly the sort of transit guy who becomes a free agent and CEO: relentlessly self-promotional and confident, any previous successes get attributed to his leadership. So he picks up stakes, gets recruited away, commands an enormous salary, and builds a brand for himself that he delivers projects on time and on budget.

Suddenly, some members of the GOP realize they actually will be part of the government

Earlier this year, leading House Republicans proposed to privatize mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac or place them in receivership starting in two years.I actually don't think the mortgage market will ever be truly a private sector enterprise. Suppose Fannie and Freddie were to go away: the most likley entities to step into the residential finance market would be banks. Would this be privitization? Not really. Banks receive explicit guarantees (FDIC) and, as we know from recent events, implicit guarantees as well (TARP was nothing if not the execution of an implicit Federal guarantee).

Now, as Republicans prepare to assume control of the House next week, they aren't in as big a rush, cautioning that withdrawing government support in the housing market should be gradual.

"We recognize that some things can be done overnight and other things can't be," said Rep. Scott Garrett (R., N.J.), incoming chairman of the House Financial Services subcommittee, which oversees Fannie and Freddie. "You have to recognize what the impact would be on the fragile housing market as it stands right now."

The conservative complaint about Fannie and Freddie is that they privatized profit while socializing risk. This is doubtless true. I just don't see how it is any less true for banks.

[update: just to be clear, I am all for FDIC, and I think on net TARP left the country better off. The point is that we will always rely on the public sector to some extent, whether some people like it or not].

Monday, December 27, 2010

Keynes on the "Psychology of Society"

Europe was so organized socially and economically as to secure the maximum accumulation of capital. While there were some continuous improvements in the daily conditions of life of the mass of the population, Society was so framed to to throw a great part of the increased income into the control of the class least likely to consume it. The new rich of the 19th century were not brought up to large expenditures, and preferred the power which investment gave them to the pleasures of immediate consumption. In fact, it was precisely the inequality of the distribution of wealth which made possible those vast accumulations of fixed wealth and of capital improvements which distinguished that age from all others. Herein lay, in fact, the main justification of the Capitalist System. If the rich had spent their new wealth on their own enjoyments, the world long ago would have found such a regime intolerable. But like bees they saved and accumulated, not less to the advantage of the whole community because they themselves held narrower ends in prospect.

The immense accumulations of fixed capital which, to the great benefit of mankind, were built up during the half century before the war [WWI], could never have come about in a Society where wealth was divided equitably. The railways of the world, which that age built as a monument to posterity, were, not less than the Pyramids of Eqypt, the work of labor which was not free to consume in immediate enjoyment the full equivalent of its efforts.

Thus this remarkable system depended for its growth on a double bluff or deception. On the one hand the laboring classes accepted from ignorance or powerlessness, or were compelled, perusade or cajoled by custom, convention, authority, and the well-established order of Society into accepting a situation in which they could call their own very little of the cake that they and Nature and the capitalists were co-operating to produce. And on the other hand the capitalist classes were allowed to call the best part of the cake theirs and were theoretically free to consume it, on the tacit underlying condition that they consumed very little of it in practice.

Wednesday, December 22, 2010

Is the Mortgage Interest Deduction a "Middle-class" benefit?

He said a couple of things, however, that bothered me. He sort of dissed renters, by saying they pay only five percent of federal income taxes, ignoring the fact that they pay FICA, state and local taxes. One would think Realtors would like renters, since they do, after all, pay rent to property owners. But he also characterized the mortgage interest deduction as being a "middle-class" deduction. This all depends on the defintion of "middle-class."

Let me turn to Eric Toder and colleagues:

The percentage reduction in after-tax income from eliminating the deduction would be largest for taxpayers in the 80th to 99th percentiles of the distribution. These upper-middle-income households would be affected more than tax units in the bottom four quintiles because they are more likely to own homes and itemize deductions and because the higher marginal tax rates they face make deductions worth more to them than to lower-income taxpayers. The very highest income taxpayers, however, will experience a relatively small drop in income (about 0.4 percent on average) because, at the very highest income levels, mortgage interest payments decline sharply as a share of income.So it is probably correct to characterize the mortgage interest deduction as an "upper-middle-class" deduction. The very rich don't benefit that much from it, because they don't really need mortgages. The bottom 80 percent don't benefit much, because their marginal tax rates are low, they are more likely to be renters and perhaps don't itemize their tax deductions. My guess is that people between the 80th and 99th percentile don't need a lot of encouragement to become homeowners.

Monday, December 20, 2010

Small reasons that government drives people crazy

At the same time, I don't hear a lot of people who are upset about how far behind schedule the project is. Maybe this is because no one is planning to take the Expo Line. Maybe it is because peoople have such low expectations of LA Metro that they are not surprised, and therefore not outraged. Either way, it suggests a problem.

I continue to believe that we need government to do certain things (rail tunnels under the Hudson and a more modern power grid, for starters) for the economy to perform well. But when government doesn't perform well, it turns positive NPV projects into negative NPV projects, and it undermines political consensus for the necessity of government.

Thursday, December 16, 2010

Bethany McLean on the GOP "primer" on the financial crisis

This narrative isn't completely wrong—but it is shockingly incomplete, which makes it, in the end, a ludicrous distortion of what happened.Three points. First, I have never, ever, seen Peter Wallison suggest that banks are ever anything by morally upright and wise, despite lots of evidence to the contrary (I would welcome a correction on this point).

Second, to say that the Affordable Housing Goals were major contributors to the crisis is silly, because as people like Wallison liked to point out, the GSE's continually lagged the market when it came to advancing mortgages to low income borrowers and underserved areas. Wallison specifically said in 2006 that GSEs were "not doing the job they should for low income borrowers. Finally, the Community Reinvestment Act did not cover many of the financial institutions that originated the most toxic loans.

What bothers me about the entire Republican narrative is that it continues a pattern of argument that suggests that when it comes to finding fault, borrowers are always more culpable than lenders; low income people are always more culpable than high income people; and underrepresented minorities somehow have gotten an unwarranted good deal.

Update: Barry Ritholtz has 10 questions for the GOP members of the commission.

Monday, December 13, 2010

Jonathan Weinstein on Fairness in Tax Policy

As a 1st approximation, someone in a highly scalable profession would keep roughly(Full disclosure: Jon is my cousin).

half their income, since they enter the game with, on average, half the population

present. (See a more carefully worked out example in the appendix.) There are

many possible adjustments to this estimate; for one, if the inventor or entertainer

is extracting rents from network e ects and they are not actually much better than

a replacement, their Shapley value might be much less than half their income. On

the other hand, someone in a non-scalable profession creates roughly the same value

regardless of the size of society, so they would keep more of their income. Whether

these considerations re

ect fairness is, of course, ultimately a value judgment, but a

50% top marginal tax rate is well within the historical range, so such an outcome

would not be radical.

The great intellectual advances that illuminated the enormous bene ts of the free

market, starting with Adam Smith and continuing into the 20th century, have long

since been assimilated into our political discourse. The danger is that in some circles

the lessons have been learned just a bit too well. The free market then becomes a

21st-century deity whose dictates are perfectly fair and should not be questioned,

lest its manna of prosperity cease to rain down upon us. Warning about this is, of

course, unnecessary for economists, who, whatever their political stripe, understand

perfectly the limits of core equivalence and welfare theorems. Keeping any nuance

is very di cult when intellectual advances are distilled for a larger population, so

responsible academics always have to be very careful in how they discuss the practical

impact of abstract results.

Yves Smith gives Five Rules for Private Label Mortgage Securitization

Yesterday's NYT: A Secretive Banking Elite Rules Trading in Derivatives

Sunday, December 12, 2010

Density and the use of public transportation

I can't help but think about a trip I made to a UN conference on urban issues. The conference took place in Barcelona, which has among the easiest to use transit systems in the world--more than half the people there live within walking distance of a metro stop. As it happens, I went to dinner with some officials from the Bush Administration, and when I suggested we use the metro instead of cabs, my companions were, well, stunned at the very idea. I pursuaded them to go, and learned that a bunch of people who lived in a city which has an excellent metro, Washington, never used public transportation.

I could be wrong, but my sense was that taking the metro in Barcelona was a foreign adventure for them in all kind of ways, and one that they did not particularly wish to repeat at home.

Friday, December 10, 2010

Monday, December 6, 2010

I see that the Adminstration's deal on taxes is being characterized as a "compromise"

Friday, December 3, 2010

The Residences at LA Live may become LA's icon

The picture comes from the LA Architecture Awards web site. I drive by this building every day, and enjoy it every day. The place still needs to stand the test of time, but I love the fact that the building is distinctive and doesn't relay on mass or extreme height to be striking.

Tuesday, November 30, 2010

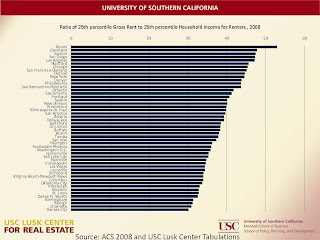

Should house prices still be falling?

If we assume the mortgage interest rate on a 30-year fixed rate mortgage is 4.5 percent, the cost of home equity is 10 percent, a buyer puts 20 percent down on a house, property taxes are one percent of house value, marginal income tax rates (state and local) are 25 percent, maintanence costs are one percent per year, and amortized closing costs are another one percent per year, the cash cost of owning is $12,162 per year.

But the median rental unit is 1300 square feet and the median owner unit is 1800 square feet, so owning the median owner unit costs about 10 percent less per square foot than renting the median rental unit. This means house prices could fall and, in some places at least, still leave the owner better off than renters.

Neither renter nor owner markets are national, but I am hard pressed to think of a time when owning on a cash-flow basis looks so reasonable relative to renting.

Monday, November 29, 2010

Ingrid Ellen, John Tye, and Mark Willis on Covered Bonds replacing GSES

Saturday, November 20, 2010

A thought experiment on airport screening and jobs

Coincidentally, Nate Silver had a blog post this week where he estimates that extra post-9-11 security screening reduced air travel by 6 percent. This begs the question as to how much impediments to movement are also impeding the broader economy.

I wrote a paper a few years back that linked passenger traffic at airports to employment. The finding was that an increase of one passenger per capita per year produced a 3 percent increase in jobs. A typical large city has four boardings per year per capita, so let's run the math: -.06*4*.03 is a .72 percent reduction in jobs. The US has about 139 million jobs, so a .72 percent reduction is about a million jobs. So it is possible that impediments to travel mean we have a million fewer people working than we otherwise would.

This is very much a first cut, rough kind of number, but it does give one pause. Is what we are doing at our airports worth sacrificing a meaningful number of jobs? Perhaps. But we should still think about the trade-offs explicitly.

Thursday, November 18, 2010

Is US success a product of bailouts?

These thoughts cross my mind as I hear people say that the solution to our mortgage problems is to get rid of non-recourse loans. We have long been more generous about bankruptcy than Europe, and it may explain why our economy is more dynamic and innovative. The US is a country about second chances in so many ways (including education); it is a country where it is OK to fail and then come back. We need to be careful about messing with that.

Monday, November 15, 2010

More BIll Cronon

He also paints vivid pictures of wheat being harvested and shipped to the White City's great grain elevators, the lumbermills of Marquette and Marrinette, of timber sliding down ice flows and floating down rivers and lakes; we can smell the entrails from the slaughtered cattle and pigs, and imagine how the Chicago River South Branch bubbles with potions not even the Weird Sisters could have imagined. He established how it became a metropolis by not becoming a new center of the center, but rather the center of the periphery.

We can see how the city raised living standards--standards that 130 years later we would (rightfully) deem appalling. His picture of Chicago, warts and all, is far more entralling than Sinclair's picture.

Couldn't we get him to do Tokyo now? Mexico City? How about Los Angeles? Kevin Starr has written a great history of California, but Cronon's angle would be different.

Sunday, November 14, 2010

Wednesday, November 10, 2010

One hand clapping for the Deficit Commission Co-chairs' powerpoint

(1) Tax expenditures are about $1.1 trillion, and deficit reduction requires scaling them back. While there has been gnashing of teeth about a proposed top marginal tax rate of 23 percet, the powerpoint contemplate this only in the context of full elimination of tax expenditures. This would surely be more efficient--it is also possible that it would be more progressive, as the biggest tax expenditures (exclusion of the employer contributions for health care, exclusion of employer contributions to pension contributions, and the mortgage interest deduction) tend to go to those with higher incomes. It is an empirical question as to how these things net out, but it is an empirical question worth answering (a similar analytical exercise was done in the middle-1990s, but the world is now different). If someone can create a tax code that brings in more revenue under static assumptions (i.e., is not projecting revenue based on Voodoo economics), is more progressive, and has lower rates because of the phase out of tax expenditures, I am all for it. FWIW, as someone who has a California mortgage and pays California state income taxes, this is probably not in my personal self-interest.

(2) I do think we need to do something about the retirement age, but it should somehow be linked to occupation. I have a cushy job, and there is no reason why I can't keep doing it until I become demented. But those who do physical labor just wear out, and it is not reasonable to ask a 60 year old lineman (the telephone kind, not the football kind) to "retrain."

Monday, November 8, 2010

Paul Willen says self-amortizing mortgages were abundant before the 1930s

It has long been "established" that self-amortizing mortgages were rare before the existence of the Home Owners Loan Corporation, whereas this source suggests they made up 40 percent of loan originations between 1925-1929. What this table doesn't tell us is how long the amortization period was. So the importance of the HOLC may have been the establishment of long-term self-amortizing mortgages.

I would love to get actual mortgage contracts with their terms from the 1920s.

A really nice paper on the Home Owners Loan Corporation

The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation purchased more than a million delinquent mortgages from private lenders between 1933 and 1936 and refinanced the loans for the borrowers. Its primary goal was to break the cycle of foreclosure, forced property sales and decreases in home values that was affecting local housing markets throughout the nation. We find that HOLC loans were targeted at local (county-level) housing markets that had experienced severe distress and that the intervention increased 1940 median home values and homeownership rates, but not new home building.

Unfortunately, the paper is behind the NBER firewall, but if you belong to a subscribing university, you can get a link to a downloadable version sent to you.

Sunday, November 7, 2010

The change in time today reminds me of one of the many things I learned from William Cronon's Nature's Metropolis

Wednesday, November 3, 2010

I comfort myself with the opening of Adam Smith's Theory of Moral Sentiments

How selfish soever man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it. Of this kind is pity or compassion, the emotion which we feel for the misery of others, when we either see it, or are made to conceive it in a very lively manner. That we often derive sorrow from the sorrow of others, is a matter of fact too obvious to require any instances to prove it; for this sentiment, like all the other original passions of human nature, is by no means confined to the virtuous and humane, though they perhaps may feel it with the most exquisite sensibility. The greatest ruffian, the most hardened violator of the laws of society, is not altogether without it.

Monday, November 1, 2010

I have started a classical music blog

http://richardsmusicblog.blogspot.com/

This is just fun for me--we will see how it works.

Please make it stop

I was listening to an Economist this AM on the radio [who is] part of a group of Economists who believe FDR's policies prolonged the Depression, rather than helped it. This goes against everything I learned in my vast High School and Community College experience. What's the real deal, Green?Just to make sure, I calculated four year GDP growth by presidential term, going back to Hoover. I count as a term as the period from inauguration to inauguration, so 1929-1933, 1933-1937, etc.

The three terms in which GDP grew fastest: FDR III, FDR I and FDR II. Even if one removes III because of the special circumstance of World War II, he still gets the best two four year periods. Do people really want to argue the counterfactual? [BTW, #4 is Truman II, and # 5 is JFK-LBJ].

On the theme of personal responsibility

People in a position to know such things tell me that one of the impediments to private renegotiation of first lien mortgages is second lien mortgage investors. If there is a place we could use a reckoning, it would be a recognition that such liens have been wiped out.

Should everyone get debt relief?

With this is mind, we should probably draw distinctions among different types of borrowers. Here is a rough ranking of borrowers in some sort of difficulty from most to least culpable for their misfortunes:

(1) Those who committed fraud: for example, those who willfully overstated their income on a loan application.

(2) Speculators who put little or no money down on a house, and then walked the instant house prices fell.

(3) Borrowers who used cash-out refinances or second liens to buy stuff--vacations, televisions, boats, etc. Michael Lacour-Little estimates that about half of underwater borrowers in Southern California took equity out of their houses.

(4) Borrowers who used cash-out refinances or second liens to pay for education or health care. Am I drawing a distinction between (3) and (4)? Yes.

(5) Borrowers who had adequate income to repay their purchase money mortgage, did not take money out of their house, lost a job (or took a serious pay cut), and are underwater.

(6) Borrowers who are current on their mortgages and are underwater. People in buckets (5) and (6) may well be equally responsible; people in (6) may have just gotten a better draw.

As a policy matter, I cannot see providing debt relief to (1)-(3). While I agree with Krugman that we cannot let worries about moral hazard prevent us from engaging in all debt relief, we cannot just ignore moral hazard altogether. The tough part, from a policy perspective, is distinguishing between (3) and (4). I am not sure how we do that, but it is worth thinking about.

As for (5) and (6), at minimum we could allow such borrowers to refinance into today's low interest rates without any fuss: this would both lower payments and the present value of the mortgage, and hence reduce the amount by which people are under water on a mark-to-market basis.

If I had my druthers, people in (5) would be offered a debt equity swap, where the amount owed (the bond) would be reduced, but a large share of any future profit would be shared with the lender. The Wisconsin Foreclosure and Debt Relief Plan is also worth considering.

Those who were treated fraudulently by lenders (particularly those who had equity stripped via fees) are in another group altogether, and deserve relief. I am not sure what the correct policy lever is for delivering it.

Friday, October 29, 2010

Where does hard-headedness end and nastiness begin?

There are a few large presumptions here: that wealth is a function of skill, and that skill is the most important criterion for determining whether one "deserves" resources. I have no doubt that there is a strong correlation between skill and wealth, but I also have no doubt that a regression where wealth is on the left hand side and skill is on the right would have a large residual.All this administration has done, in effect, is additionally regulate banks and businesses (in the middle of a deep recession) and transfer resources from high skill to low skill. That's what the health care plan and the extension of unemployment benefits has done.

But even if skill translated perfectly to wealth, I am uncomfortable with the idea that the unskilled are unworthy of having a decent standard of living, particularly in a country as rich as the United States. I also think that income distribution data from OECD calls into serious question whether rewarding the "highly skilled" leads to better outcomes for the lower income parts of society. Thus I recoil at the idea that extending unemployment insurance periods in times when there are far more job seekers than jobs is a good idea.

That said, the hard-headed aspects of economics do lead to important insights. For example, when the country is at full-employment (or something like it), the duration of unemployment insurance should be limited, because we do want people to work. Similarly, we should always make it better for people to work than to receive government assistance. I could also go on about the evils of rent control, etc.

This is where I feel conflicted about my discipline on a regular basis. So much of what we put out there strikes me as being on its face inhumane and arrogant. Yet I would hate to see what policy would look like in our absence.

Thursday, October 28, 2010

Sampling

Wednesday, October 27, 2010

The real reason why a foreclosure moratorium would be a bad idea

(1) A moratorium would slow down the eventual resolution of the housing crisis;

(2) A moratorium would add yet another level of uncertainty about the ability to foreclose going forward, which would discourage the private sector from returning to the mortgage market. If lenders can't take away the houses of people who don't make their payments, they will not advance mortgage money in the first place.

But last night it occurred to me why I have such a visceral reaction to such things as moratoriums: they strip property rights without due process. If a borrower agrees to repay a mortgage, and everything about the mortgage is legitimate, and the borrower ceases to make payments, the lender has a property right to take the house.

I am at times a card-carrying member of the ACLU, because I think the rule of law and due process should apply to everyone. Many lenders have behaved badly and appear to still be behaving badly. That doesn't mean that all of them should lose their well-defined rights--even temporarily.

Monday, October 25, 2010

Why to avoid motorcycle riding in India

I

saw someone die in the street last night.

During orientation, Robert explained the five Buddhist Precepts to us, and he explained why our experience and that of others would be better if we agreed to follow them during our time here. Then he said that if we broke one, we shouldn’t beat ourselves up, but that we should try not to do it again. When a few students were caught drinking and smoking on the roof, he said at lunch that he’d heard about it, and that if we had any intoxicants in our room we should go get them and flush them down the toilet. He didn’t say to go get them and bring them to him. He understands that he can’t make us do anything.

The only thing that he forbade expressly was riding motorcycles.

“Riding a motorcycle in India is the most dangerous thing you can do,” he said. “There is no trauma ward. If you get into an accident, everyone will stand and watch while you bleed to death in the street.

I saw the crowd before I saw the body. I was walking with a couple of French people I’d met the night before. They saw the crowd and didn’t wish to walk that way. One man told me it was OK for us to pass, so I went because otherwise I would be late to mediation. For just half a second I saw the man lying exactly on his back in a pool of blood with a thick stream of blood draped across his face and body. It could not have been more red. His motorcycle was behind him. I turned my head away and touched the wall next to me, but the image has not left my mind. This body was not like a body prepared for cremation in Varinassi. They were supposed to be dead. This man was still fresh. He should have been alive. At the moment I saw him, maybe he was alive.

I walked back the way I’d come and saw my fellow students coming toward me in rickshaws. I looked at them and said “there’s a dead man in the street.” I expected them to stop or something, but the rickshaws just went past. Only Wanda and Heidi got out. I didn’t want to walk alone, so I had to walk past the same place to catch up with them. The body was being carried up the hill on a woven stretcher, and I had to see the pool of blood mixed in the gravel and rainwater again as I walked past.

When we got to mediation we were having a group photo taken. We had to wear our Zen robes. I thought “I can’t figure out the strings on these robes, I just saw a dead man,” and “I can’t smile for this photo, there was so much blood,” and “I can’t get up for walking mediation, he was lying right on his back like he was in bed,” but I managed to do all those things anyway.

It was our final meditation session in the Japanese temple, so afterward one of the monks spoke to us. He told us that “Arigato” means more than thank you in Japanese. It means, these circumstances were difficult to come by, and we are so happy that you can be here. You are not just thanking the person you are speaking to, but you are thanking every circumstance that lead you to be together. He said we should all call or e-mail our families to say “arigato”. He said that it might confuse them, but he didn’t care. Maybe it’s wrong, but it’s true that seeing death like that makes you understand how rare it is that so many of the people you love are still healthy and fine. Arigato.

Thursday, October 21, 2010

The Fannie-Freddie Problem is not as severe as the headlines would suggest

Wednesday, October 20, 2010

Second Annual UCI-UCLA-USC Urban Research Day

October 22nd, 2010

Ralph & Goldy Lewis Hall 100

8:30 am

Continental Breakfast

Session 1

9:00 am - 11:00 am

Kerry Vandell (University of California, Irvine)

" Tax Structure and Natural Vacancy Rates in the Commercial Real Estate Market: Can Tax Incentives Cause Overbuilding in a World of Stochastic Prices”

Discussant:

Gary Painter (University of Southern California)

Stuart Gabriel (University of California, Los Angeles)

"Housing Risk and Return: Estimates of a Housing Asset Pricing Model"

Discussant:

Xudong An (San Diego State University)

Break 11:00 am – 11:10 am

Session 2

11:10 am – 12:10 pm

Ryan Vaughn (University of California, Los Angeles)

“Strategic Foreclosure: An Empirical Assessment of

Strategic Behavior by Lenders in the Mortgage Market”

Discussant:

Chris Redfearn (University of Southern California)

Session 3

1:15 pm – 2:15 pm

Richard Green (University of Southern California)

“Surfing for Scores: School Quality, Housing Prices, and the Changing Cost of Information” with Paul Carrillo and Stephanie R. Cellini

Discussant:

Matthew Kahn (University of California, Los Angeles)

Break 2:15 pm – 2:25 pm

Session 4

2:25 pm – 3:25 pm

Jenny Scheutz (University of Southern California)

“Is the 'Shop Around the Corner' a Luxury or a Nuisance?The relationship between income and neighborhood

retail patterns” with Jed Kolko and Rachel Meltzer

Discussant:

Jan Brueckner (University of California, Irvine)

Break 3:25 pm – 3:35 pm

3:35 pm – 4:30 pm

Session 5

Marlon Boarnet (University of California, Irvine)

“ Land Use and Vehicle Miles of Travel in the Climate

Change Debate: Getting Smarter than Your Average

Bear”

Discussant:

Lisa Schweitzer (University of Southern California)

Dinner 6:00 pm

Location Café Pinot

Minutes vs Stress

Today was a bad day in LA--it rained, and people just don't know how to deal with that here. But for some reason, I found commuting by car in DC to be far more frustrating. In both cities, the distance between my home and office was about the same. As it happens, I hated driving in DC so much that I took Metro to work nearly every day, and the total Metro commute was about 50 minutes one way (including walking). On the other hand, the walk from my house to the Bethesda Metro station and from Dupont Circle to my office in Foggy Bottom was quite pleasant.

But back to the point--somehow driving in LA seems far less stressful to me than driving in Washington. Maybe it's just that the radio stations are better....

Sunday, October 17, 2010

Read Yves Smith

Friday, October 15, 2010

Monday, October 11, 2010

I wish I could give credit where it is due

Sunday, October 10, 2010

Greg Mankiw forgets about the income effect

This is the substitution effect--because leisure becomes relatively cheaper, people consume more of it. But higher taxes also reduce after-tax income (obviously), so in order to maintain living standards, one might decide to work more in the face of higher taxes. This is called the income effect. I can speak for my household--our after-tax income is more than sufficient for our "needs," but if we were taxed more, we might have to work more to satisfy these "needs."

It is an empirical question as to whether within certain ranges of tax rates, raising taxes increases or reduces effort. Theory gives us an ambiguous answer. (h/t Mark Thoma).